Metaxas' essential tome on the life of William Wilberforce is not an easy read. His categoric description of Wilberforce's life is thick with minute details and a sometimes overwrought narrative that can make it a challenge to wade through its pages. This is not to take away from the skill of Metaxas--my reading tastes just happen to run more Hemingway than Faulkner--and Metaxas falls squarely in the Sound and the Fury school. Regardless I don't know many authors out there today with the researching acumen of Metaxas--one has only to read his untouchable Bonhoeffer to be assured of this. He's also someone that takes morality seriously but does it in a manner that is humorous and approachable. It'd be worthwhile to check out his podcast/radio show as well. He's on twitter too.

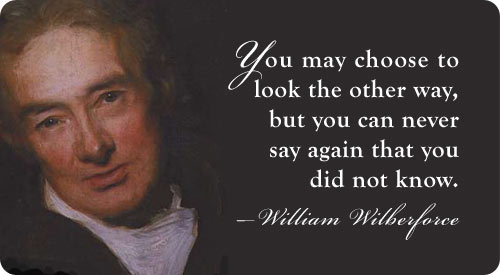

The complexity of his writing shouldn't dissuade you from reading Amazing Grace--committing to the marathon is a worthwhile endeavor because of the magnitude of what Wilberforce accomplished. This man's entire life itself was one tireless long-distance race dedicated to a near singular cause--abolishing slavery in England.

To put Wilberforce's life story into perspective, imagine today if a Matt Damon/Conan O'Brien/James Franco/Ben Carson combo of a person was elected as a senator from California and then eventually dropped his hard-partying ways after finding Jesus and then dedicates his next three decades to ending the largest social travesty in existence at the time...something like abortion today. But further imagine that he didn't work tirelessly just to end abortion legislatively but worked just as tirelessly to build a social and financial support and safety net for the hundreds of thousands of mothers (and their babies) faced with an incredibly difficult decision with an unplanned pregnancy--that was his heart and tenacity.

Amazing Grace by Eric Metexas

As one might imagine, Whitefield was despised by the Church of England. But the press and those opposed to religion hated him too. He didn’t mince words on the subjects of sin and hell, and he was increasingly impossible to avoid as his fame grew and grew. Whitefield was forever on the march, like some one-man salvation army. He carried a collapsible pulpit with him and sent handbills and posters ahead to the towns where he would preach; in his lifetime, he preached eighteen thousand sermons, none dull. Read more at location 352

Wit and its employment as a weapon not only in political

combat but in playing with one’s friends was at the core of the Goostree’s

Gang. Their favorite pastime was trading quips and being witty—what they called

“foyning,” or “foining.” The term “to foin”—originally French—means to thrust,

as with a rapier sword. “Foining” swordplay with lighter swords and rapiers had

replaced the earlier kind of swordplay with broadswords, which involved cutting

and slashing. So “to foin” meant to parry deftly and thrust with one’s wits;

the term “rapier wit” is a cousin of “foining.” It was an era in which wit was

greatly valued, and Wilberforce and his friends, all inveterate wits, were

dubbed by Edward Eliot “the Foinsters. Read more at location 662

1782 Gerard Edwards wrote: “I thank God that I live in the

age of Wilberforce and that I know one man at least who is both moral and

entertaining. Read more at location

692

Ideas have far-reaching consequences, and one must be ever

so careful about what one allows to lodge in one’s brain. Read more at location 1069

Wilberforce’s “Great Change” did not happen overnight or in

an instant. St. Paul might have been blinded by the light and changed in a

single moment that could, in effect, be captured in a painting, but

Wilberforce’s transformation was much more gradual. His conversion was much

closer to St. Augustine’s, who came to intellectual clarity about the doctrines

of Christian faith but was frustrated by his inability to conform his behavior

to his beliefs. “I got a clear idea of the doctrines of Religion,” Wilberforce

wrote years later, “perhaps clearer than I have had since, but it was quite in

my head. Read more at location 1100

What he needed desperately was someone to whom he might

unburden himself, someone who would understand and know what to do, someone

with the wisdom to remind him of what he needed to be reminded of just now—of

God’s grace—of the upside of God’s love.

Read more at location 1137

November 29: “Pride is my greatest stumbling block; and

there is danger in it in two ways—lest it should make me desist from a

christian life, through fear of the world, my friends, &c; or if I

persevere, lest it should make me vain of so doing. Read more at location 1155

gives us a strong hint of the contents of Wilberforce’s

letter, as well as an extraordinary picture of Pitt at this time and of the

intimacy of their friendship: My dear Wilberforce, Read more at location 1179

For you confess that the character of religion is not a

gloomy one, and that it is not that of an enthusiast. But why then this

preparation of solitude, which can hardly avoid tincturing the mind either with

melancholy or superstition? If a Christian may act in the several relations of

life, must he seclude himself for all to become so? Surely the principles as

well as the practice of Christianity are simple, and lead not to meditation

only but to action. Read more at

location 1194

Newton didn’t tell him what he had expected—that to follow

God he would have to leave politics. On the contrary, Newton encouraged

Wilberforce to stay where he was, saying that God could use him there. Most

others in Newton’s place would likely have insisted that Wilberforce pull away

from the very place where his salt and light were most needed. How good that

Newton did not. Wilberforce writes afterward: “When I came away I found my mind

in a calm, tranquil state, more humbled, and looking more devoutly up to God. Read more at location 1226

Two changes manifested themselves right away: the first was

a new attitude toward money, the second toward time. Before “the Great Change,”

Wilberforce had reckoned his money and time his own, to do with as he pleased,

and had lived accordingly. But suddenly he knew that this could no longer be

the case. The Scriptures were plain and could not be gainsaid on this most

basic point: all that was his—his wealth, his talents, his time—was not really

his. It all belonged to God and had been given to him to use for God’s purposes

and according to God’s will. God had blessed him so that he, in turn, might

bless others, especially those less fortunate than himself. This new attitude

toward Read more at location 1265

As we shall see, in Wilberforce’s day, it was devout

Christians almost exclusively who were concerned with helping the poor,

bringing them education and acting as their advocates, and who labored to end

the slave trade, among other evils. But so successful would Wilberforce and

these other Christians be at bringing a concern for the poor and a social

conscience into the society at large that by the next century, during the

Victorian era, this attitude would become culturally mainstream. Read more at location 1287

God, in his mercy, had allowed Wilberforce to see himself as

he truly was, and it was crushing. But Wilberforce knew God didn’t mean to end

there. On the other side of the worst of who he was, if he dared face that

worst, was a God who would help him overcome his faults and do great things,

the very things for which he had created him. It was not too late. Read more at location 1333

one point he entered into a pact with Milner to “exercise

the invaluable practice of telling each other what each party believes to be

the other’s chief faults and infirmities.

Read more at location 1338

Newton wrote Wilberforce a letter sometime later that seemed

to sum up his view of the situation. “It is hoped and believed,” he famously

wrote, “that the Lord has raised you up for the good of His church and for the

good of the nation.” Pitt, in his letter, had said something similar: “Surely

the principles as well as the Read more

at location 1349

practice of Christianity are simple and lead not to

meditation only, but to action. Read

more at location 1351

Wilberforce’s decision to remain in politics made the

transfer of Christian ideas into the previously “secular” realm of society

possible for generations of Christians to follow. Read more at location 1354

Entirely surprising to most of us, life in

eighteenth-century Britain was particularly brutal, decadent, violent, and

vulgar. Slavery was only the worst of a host of societal evils that included

epidemic alcoholism, child prostitution, child labor, frequent public

executions for petty crimes, public dissections and burnings of executed

criminals, and unspeakable public cruelty to animals. Read more at location 1370

When eighteenth-century British society had retreated from

the historical Christianity it had earlier embraced, the Christian character of

the nation—which had given Britain, among other things, a proud tradition of

almshouses to help the poor, dating all the way back to the tenth century—had

all but disappeared. The almshouses remained, and the outward trappings of

religion remained, but robust Christianity, with its noble impulses to care for

the suffering and less fortunate, was gone.

Read more at location 1391

The barbarous custom of hanging has been tried too long, and

with the success which might have been expected from it. The most effectual way

to prevent greater crimes is by punishing the smaller, and by endeavouring to

repress that general spirit of licentiousness, which is the parent of every

species of vice. I know that by regulating the external conduct we do not at

first change the hearts of men, but even they are ultimately to be wrought upon

by these means, and we should at least so far remove the obtrusiveness of the temptation,

that it may not provoke the appetite, which might otherwise be dormant and

inactive. Read more at location

1519

What made this royal proclamation—and the formation of

proclamation societies—so important was that it furthered two parts of

Wilberforce’s plan: his “broken windows” analysis of the condition of the poor,

and his quest to “make goodness fashionable.” It helped the “broken windows”

part of his plan by addressing the fact that the Crown almost never brought

suit against anyone. Read more at

location 1566

By June 1787, Wilberforce had already taken many steps on

the very long journey ahead toward the “reformation of manners.” In fact, it

wasn’t until October 28 that he coined that phrase, when he famously penned in

his diary: “God almighty has set before me two great objects: the suppression

of the slave trade and the reformation of manners. Read more at location 1601

Granville Sharp was one of those Christian fanatics who took

the injunction to love one’s neighbor literally—who loved his neighbors even

when they were inconvenient African neighbors trying to reclaim their freedom.

Of course, word of his literal interpretation traveled quickly, and slaves who

had heard of Sharp and his work sought him out. Granville Sharp was of course

thrilled to be doing the Lord’s work in freeing these poor souls—and each case

provided a fresh opportunity to do the wider good of improving the vexingly weedy

British legal system. Read more at

location 1749

“I well remember,” Wilberforce wrote years later, “after a

conversation in the open air at the root of an old tree at Holwood, just above

the steep descent into the vale of Keston, I resolved to give notice on a fit

occasion in the house of Commons of my intention to bring the subject forward.”

And thus, history: three men, each named William, each twenty-seven years old,

talking at the base of an ancient oak tree on a hill in May: one prime

minister, one prime-minister-to-be, and one who would stand from that moment

forward at the center of something so big and beyond any single man that a tree

whose life had begun several centuries earlier, and would continue for nearly

two more, was the humble creature chosen to bear mute witness to the

conversation. Read more at location

2044

That same year, and perhaps just in time, Henry Thornton had

invited Wilberforce to move with him into Battersea Rise, Thornton’s home in

Clapham. Thornton called it a “chummery”—a place where bachelors lived

together. They would live together for the next four years, sharing the upkeep

of the place. Edward Eliot would live next door, in a house called Broomfield

Lodge, and Charles Grant would live in yet a third house. Thus began the

Clapham Community, which has also been called the Clapham Sect, the Clapham

Circle, the Clapham Saints, the Claphamites, and other things, good and bad. Read more at location 2566

When he was through, Fox rose and flew at Dundas with all of

his considerable oratorical skills, mocking the idea of moderation in such

things as murder and atrocity. “I believe [the slave trade] to be impolitic,”

Fox said. I know it to be inhuman. I am certain it is unjust. I find it so

inhuman and unjust that, if the colonies cannot be cultivated without it, they

ought not to be cultivated at all…. As long as I have a voice to speak, this

question shall never be at rest…. and if I and my friends should die before

they have attained their glorious object, I hope there will never be wanting

men alive to do their duty, who will continue to labour till the evil shall be

wholly done away. It was a powerful peroration from Fox, a crackling bonfire of

truth and clarity, and it was much needed. His words shone a great deal of

light onto the moral cowardice of “regulation” and the lazy wickedness of

“moderation.” But the canny Scotchman was not troubled. Dundas had thrown water

on fires before and knew that one needn’t extinguish the whole fire; sometimes

simply creating enough smoke would do all that was needed. Everyone would

leave, and then the idiot fire could burn and illuminate the blessed

nothingness around it all night long!

Read more at location 2615

And so a motion was passed, 230 to 85, in favor of gradual

abolition. All Wilberforce could do was wonder how it had happened and stare at

the empty plate on the table where the sausage had lain. Three weeks later,

“gradual” was determined to mean by January 1796. Many expressed their hearty

congratulations to Wilberforce that abolition had finally been “approved,” but

for Wilberforce it was confusing. Was this indeed some kind of triumph, after

all, for which to be grateful, or was it an abject and heartbreaking failure to

do what they had tried and tried to do since 1787, Read more at location 2647

Indeed, as far as Wilberforce was concerned, faith in Jesus

Christ was the central and most important thing in life itself, so it can

hardly surprise us that sharing this faith with others was central and

important to Wilberforce too. And so, everywhere he went, and with everyone he

met, he tried, as best he could, to bring the conversation around to the

question of eternity. Wilberforce would prepare lists of his friends’ names and

next to the entries make notes on how he might best encourage them in their

faith, if they had faith, and toward a faith if they still had none. He would

list subjects he could bring up with each friend that might launch them into a

conversation about spiritual issues. He even called these subjects and

questions “launchers” and was always looking for opportunities to introduce

them. Read more at location 2858

Wilberforce wanted to point out the logical disconnect, to

show the vast gulf separating “real Christianity,” as he called it, from the

ersatz “religious system” that prevailed in its place. The book’s long title, A

Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in

the Higher and Middle Classes in This Country, Contrasted with Real

Christianity, made it difficult to miss the point. Read more at location 2899

Wilberforce explained that real Christianity had evaporated

from England principally because it was woven into the social fabric and

therefore was easier to ignore and take for granted. “Christianity especially,”

he wrote, “has always thrived under persecution. For then it has no lukewarm professors.”

Wilberforce was exactly right. Not Read

more at location 2912

For those who believe in random coincidences, it was an

extraordinary coincidence by any account that on the day after registering what

for him was a very rare sense of peace with God that he should meet the woman

for whom he had been waiting and praying so many years. For it was that next

day, Holy Saturday, that Wilberforce met his future wife for the very first

time. They dined in a party, and before all of the courses had been served

Wilberforce had fallen headlong for her, and eight days later they were

engaged, and a month after that married—and within ten years had six children,

four boys and two girls. But we may be getting ahead of ourselves. Read more at location 2995

Jacta est alea. [The die is cast.] I believe indeed she is

admirably suited to me, and there are many circumstances which seem to advise

the step. I trust God will bless me; I go to pray to Him. Read more at location 3021

but inasmuch as love covereth a multitude of sins, it

covereth a smaller number too. Read more

at location 3052

The central feature of Battersea Rise was the oval library.

The oval was a highly fashionable shape at the tail end of the eighteenth

century, the most popular example of which, of course, is the Oval Office in

the White House. The oval shape was used for very special rooms because it

enables a dignitary or honoree to be surrounded by a circle of admirers without

seeming to have a favorite. Read more at

location 3118

The Clapham Circle was involved in a seemingly endless

number of ventures, but at the center, always, was the fight for abolition and

the slaves. One of the projects closest to the heart of the abolition movement

was the establishment, with great effort and difficulty, of a free and

self-governing colony of former slaves in Sierra Leone, a venture whose

beginnings predated Wilberforce’s involvement in the abolitionist cause. On May

10, 1787, two days before the famous conversation under the oak at Holwood, a

ship full of former slaves had dropped anchor off the coast of Sierra Leone.

But of course, this experiment, for such it was, had originated long before

that. Read more at location 3221

Wilberforce was now forty-seven years old, but for someone

who’d been part of a veritable youth movement—a boys’ club that had taken over

Parliament—he was now practically an old man. And he felt it too. His always

frail body, which had been wracked with pain and discomfort ever since he could

remember, was the body of someone much further along in years. The constant

doses of opium pushed on him by his doctors for his ulcerative colitis had

taken their toll on his eyes, and the curvature of his spine and the telltale

slump of his head that would mark him in later years were already discernible.

He’d entered Parliament as a boy of twenty-one, fresh from the bright green

lawns of Cambridge—but how the years and battles had aged him! As if to

underscore things, Pitt, his ally and friend since those carefree days, was

dead, and from complications brought on by gout, an old man’s disease. Read more at location 3449

Everyone caught up in the increasingly charged atmosphere

had been waiting, as it were, for some unconscious cue, something to ground the

electricity—and Wilberforce’s tears were it. Almost simultaneously, every man

in the chamber lost his composure and was carried off by the flood of emotion.

Everyone rose, and three deafening cheers rang out for Mr. Wilberforce; they

echoed off those historic walls and hallowed them, and all was lost to the tumult. Read more at location 3537

abolition, and the battle would be officially won. But let’s

not run ahead just yet. Let’s behold him here for a little while longer, here

in this Moment of moments, a man allowed that highest and rarest privilege, to

be awake inside his own dream. Seated there, head in his hands, humbled and

exalted in his humility, we have the apotheosis of William Wilberforce. After

this historic victory, Read more at

location 3549

The Irish historian William Lecky gives us his own

oft-quoted verdict: “The unweary, unostentatious, and inglorious crusade of

England against slavery may probably be regarded as among the three or four

perfectly virtuous pages comprised in the history of nations.” Read more at location 3581

But as this wider African venture gained traction, it became

painfully clear that the immediate problem would be enforcing abolition. Those

who had been involved in the lucrative slave trade were not about to give it up

without a fight, and much smuggling was going on. British slavers used every

devious stratagem, the first of which was flying the American flag as they

sailed so that Royal Navy patrols wouldn’t bother them. Under the false colors

of the Stars and Stripes, thousands of Africans continued to suffer the Middle

Passage and were sold into West Indian slavery.

Read more at location 3610

The Royal Navy would become the policemen of the high seas

for many decades into the future, and incredible as it may seem, British

patrols were still functioning in this noble capacity into the 1920s. By then

the large-scale trade had disappeared, but enterprising criminals will find

niche markets. Each year into the 1920s ten or twelve boats, each carrying

fifteen to twenty children, mostly for sale into the sex trade, would cross the

Red Sea from Eritrea up into Saudi Arabia.

Read more at location 3622

Wilberforce loved memorizing poetry, Cowper and Milton

especially, and he often recited it as he walked. But he especially enjoyed

reciting Scripture and took seriously the injunction—from Psalm 119 itself—to

“hide God’s word in one’s heart.” Read

more at location 3640

After Perceval’s assassination, another dissolution of

Parliament seemed imminent, and another election. Wilberforce was forced to

think about his position as MP for Yorkshire and the great responsibilities

that it entailed. He was in his twenty-eighth year in his Yorkshire seat,

having entered upon that role in 1784, the year before his “Great Change.” He

had been twenty-four then, and was now fifty-two, with six children. The

exigencies of his political position forced Wilberforce to spend much time away

from his family, far too much time, he thought. Once when Wilberforce picked up

one of his little sons, the child had cried, and the boy’s nursemaid had

helpfully explained, “He always is afraid of strangers.” Read more at location 3677

Both Wilberforce’s habit of twice each day conducting family

prayers—with everyone kneeling against chairs for the ten minutes or so that

they took—and his regard for the Sabbath as a time to be spent with one’s

family went a long way toward establishing these practices as a model for many

in nineteenth-century Britain. Read more

at location 3739

and he denounced the East India Company’s reprehensible

refusal to lift a finger “to enlighten and reform them” while they suffered

“under the grossest, the darkest, and most depraving system of idolatrous

superstition that almost ever existed upon earth.” Wilberforce was speaking

less of Hindu theology than of the barbaric cruelties of East Indian culture at

the time, including the common practices of female infanticide and suttee, in

which a widow was bound and burned alive on her husband’s funeral pyre.

Moreover, the caste system Read more at

location 3770

When Wilberforce entered Parliament, there were three MPs

who would have identified themselves as seriously Christian, but half a century

later there were closer to two hundred.

Read more at location 3882

Czar Alexander was in his mid-thirties and was an

evangelical Christian too, though with leanings toward mysticism and

apocalyptic thinking of which Wilberforce would have been dubious. Read more at location 3967

When his turn came to address the crowd, Wilberforce stood

and before their eyes the frail little man blossomed into the impassioned and

vigorous orator they had always known—and he inspired the jostling assemblage

to a resolution: they would petition Parliament to amend the peace treaty, to

remove the clause allowing the French five more years of the trade. The MPs in

the room were mostly Whigs, and in a grand gesture of political bipartisanship

they determined that they would not present their own petition to Parliament,

which might embarrass their Tory counterparts. Instead, Wilberforce should

present it, and they now hailed him, movingly, as “the father of our great

cause.” Read more at location 3991

strife that when the news reached London, it was very emotional

for Wilberforce. The American inventor Samuel Morse, who gave us the telegraph

and the Morse code, was a friend of Wilberforce’s and was visiting him that

very day for dinner at Kensington Gore. Zachary Macaulay was there, along with

Charles Grant and his two sons. When Morse arrived, he had just walked through

Hyde Park and had seen crowds gathering. The rumors were that Napoleon had been

captured and the war was over. But Wilberforce, cautious as ever, couldn’t

believe it. “It is too good to be true,” he said. “It cannot be true.” Read more at location 4040

As for abolition, there was even better news. The Bourbon

government, once again restored, did not rescind Napoleon’s decree abolishing

the French trade. For his glorious victory on the muddy field at Waterloo,

Wellington’s stature had grown greatly in Europe’s eyes. This, among other

things, had turned the tide. Castlereagh had reapplied pressure for abolition

with Talleyrand, and in the end the French king felt compelled to confirm

abolition once and for all. On July 31, 1815, Castlereagh wrote to Wilberforce,

“I have the gratification of acquainting you that the long desired object is

accomplished and that the present messenger carries to Lord Liverpool the unqualified

and total Abolition of the Slave Trade throughout the dominions of France.”

This Read more at location 4052

“This is not our friend. This is but the earthly garment

which he has thrown off. The man himself, the vital spirit has already begun to

be clothed with immortality.” Read more

at location 4086

Like many struggles, the battle for abolition was fought in

people’s minds as much as in the halls of Parliament. Wilberforce knew most

people would not believe blacks could be free citizens entrusted to the

formidable task of governing themselves, but if these skeptics saw it, they

wouldn’t have any choice. This was why Sierra Leone was a symbol of supreme

importance, and worth all of the endless trouble it caused. But in 1811 the

island state of Haiti—formerly Saint-Domingue—presented the cause of abolition

with a second signal opportunity to show the world that African blacks could be

their own masters, and in the slave owners’ backyard too. It was in that year

that Henri Christophe, a former slave who had risen in the ranks of the

revolutionary army, suddenly found himself at the head of the country. Read more at location 4102

Christophe everything from virus vaccines, with instructions

on how to vaccinate, to special New Testaments they had prepared with

side-by-side French and English translations. They sent a copy of the British

Encyclopedia, and Wilberforce continued to send letters offering advice on

everything that related to the great project—including a plea to Christophe to

do something many might have found scandalous: he persuaded him to educate the

women of Haiti Read more at location

4124

But now, in 1818, it could be seen that this hope had been

naive. So once again the course was clear: immediate emancipation by political

means. Read more at location 4193

So Wilberforce stepped into the breach. He put forward a motion

in the House, wrote another MP, “upon pure motives of charity to spare the

public the horrid and disgusting details of the King’s green bag and of the

green bag which the Queen might bring against the King.” A trial would open a

Pandora’s box of venereal furies. But the king and queen hardly seemed to give

a fig for how their actions might harm the nation. Read more at location 4268

The king’s final offer was a large sum of cash, in return

for which he expected the queen to go away forever. She could use the title of

“Queen” wherever she roamed and would have a royal yacht at her disposal, a

frigate, etc. But there was one thing the king would not give her, one

concession he would not make: he emphatically refused to allow her name to be

read Read more at location 4271

Later that summer, Wilberforce came face-to-face with

another happy “alleviation,” much like the moss-rose, though he in no wise

could have appreciated the larger significance of it at the time. Just before

departing with his family for Weymouth, Wilberforce was invited to call on the

Duchess of Kent. “She received me,” he writes, “with her fine animated child on

the floor by her with its playthings, of which I soon became one.” How like

Wilberforce to stoop to the floor at sixty and engage an infant, but had he

known whom he entertained there on the floor, he might have sung the Nunc

Dimittis and departed in peace for Weymouth. For the rosy-faced,

German-speaking Read more at location

4337

fourteen-month-old was none other than the future Queen

Victoria, whose cherubic countenance was as unlike Queen Caroline’s countenance

as that glorious moss-rose. And so here, on the miniature plain of the carpet,

in a prophetically fitting tableau of domestic happiness, the child who would

lend the future era her name met the man who would lend it his character. Read more at location 4341

Though it would have surprised Wilberforce, two of his sons,

Henry and Robert, would be involved in the Oxford Movement and later in life be

received into the Catholic Church. But it was the battle for Read more at location 4370

Throughout his life Wilberforce resisted the cheap

temptation to point the finger at others while posturing as their moral

superior. He succeeded in defusing the anger of some and drew them in to hear

what he was saying. Cobbett, however, was never one of them; he called Read more at location 4376

Wilberforce knew he was not the man to lead the final

parliamentary push toward emancipation. It would be wiser to appoint—and in his

case, perhaps anoint—a successor. The oil would be drizzled upon the head of

Thomas Fowell Buxton, a devout evangelical MP who was politically independent,

like Wilberforce, but who, unlike him, was young, vigorous, and healthy, having

been born in 1786. Read more at location

4388

Nor did his concern for the well-being of others end with

his own species. Wilberforce’s home was a menagerie of animals that included

rabbits, turtles, and even a fox. In 1824—along with his successor in the

abolition struggle, Thomas Fowell Buxton—he was one of the founding members of

the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Read more at location 4404

has been so heavy as to compel me to descend from my present

level and greatly to diminish my establishment. But I am bound to recognise in

this dispensation the gracious mitigation of the severity of the stroke. Mrs.

Wilberforce and I are supplied with a delightful asylum under the roofs of two

of our own children. And what better could we desire? A kind Providence has

enabled me with truth to adopt the declaration of David, that goodness and

mercy have followed me all my days. And now, when the cup presented to me has

some bitter ingredients, yet surely no draught can be deemed distasteful which

comes from such a hand, and contains such grateful infusions as those of social

intercourse and the sweet endearments of filial gratitude and affection. Read more at location 4447

But others aren’t obliged to be so modest about him. In the

estimation of Sir Reginald Coupland, who was Beit Professor of Colonial History

at Oxford, “more than any man, he had founded in the conscience of the British

people a tradition of humanity and of responsibility towards the weak and

backward…whose fate lay in their hands. And that tradition has never died.” As

well versed as we are today in the manifold failings of colonial rule, the

comparison to things before Wilberforce gives us another picture. Before

Wilberforce, a world power like Great Britain could do what it liked with the

people of Asia and Africa, and for two centuries and more did, treating human

beings as they treated dumb beasts or insensate resources like timber, hemp,

and ore; but after Wilberforce, all that changed. What “Wilberforce and his

friends achieved…” Coupland tells us, “was nothing less, indeed, than a moral

revolution.” Read more at location

4523

and go down to the grave amid the benedictions of the poor. Read more at location 4577

One year later Wilberforce would have his greatest memorial,

and the one for which, unashamedly, he had labored. Sir Reginald Coupland

describes it in the last words of his 1923 biography: “A year later, at

midnight on July 31, 1834, eight hundred thousand slaves became free. It was

more than a great event in African or in British history. It was one of the

greatest events in the history of mankind.”

Read more at location 4578

And yet these are all but shadows of the things that once

were. To all of us wandering together here now, looking for William

Wilberforce, I repeat the words Wilberforce repeated to himself that day when

standing near the lifeless body of his own departed friend, Henry Thornton:

“Why seek ye the living among the dead? He is not here. He is risen.” Read more at location 4674

No comments:

Post a Comment